Learning Design Insights from Outer Wilds

Curiosity, Autonomy, Growth Mindset, and Intrinsic Motivation

Outer Wilds is a curiosity-driven space exploration game. According to Wikipedia, "The game was listed as one of the best games of 2019 by several publications, and Edge, Polygon and Paste also featured it on their 'best games of the decade' lists." Not only is it a great game but I think it contains insights about how to design learning experiences. Outer Wilds pursued some very interesting design goals. It offers an environment that:

- Evokes the player's curiosity. Gets them to ask and pursue their own questions. Gets them to formulate their own objectives. Never explicitly tells the player what to do.

- Rewards the player solely with knowledge. It is completely absent of any extrinsic rewards.

- Fosters the player's growth mindset through experiences and role models.

First, I'll give a brief description of the game's premise and then we'll analyze the game from the perspective of designing learning experiences.

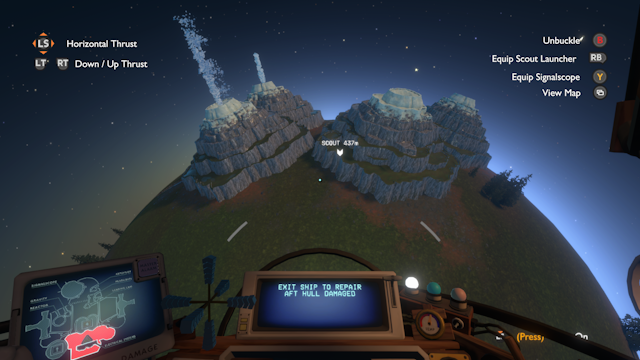

In Outer Wilds, you play as a member of an alien species who has just joined Outer Wilds Ventures, a small space program of solo explorers that are searching for answers in their solar system. You get your own tiny ship and you're off to explore whatever attracts your interest. The solar system and its handful of planets are relatively small so you explore it all over the course of the 20 or so hours it takes to complete the game. It only takes a minute or two to travel across the whole solar system.

Playing the game feels something like this. You land on a planet, you begin exploring it, and you spot something interesting. You learn a little bit from this interesting thing and it leaves you a clue for where to learn more, often on another planet. Through pursuing the clue, you acquire a little bit more knowledge and another clue of where to learn even more. Through continuing this cycle of intentional exploration, you end up discovering answers to the game's major narrative questions.

Next we'll look in detail at a number of ways in which Outer Wilds is interesting from the perspective of designing learning experiences:

- No extrinsic rewards. Curiosity is the player's sole motivation, knowledge the sole reward.

- Experiential growth mindset. Communicating the perspective of failure as progress without the use of any explicit instructions.

- Emphasis on player autonomy. Evoking the player's curiosity and getting them to ask their own questions. Never explicitly telling them what to do.

- Architecting for the piquing of curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge. High level design techniques for evoking the player's curiosity and providing clues for them to pursue it.

- Ship log: a map of the player's knowledge. Helping the player to remember what they've learned so far and what they might want to explore next.

No extrinsic rewards

Here are some rough definitions of intrinsic reward and extrinsic reward:

- Intrinsic reward: The activity itself is its own reward. Example: I read books just because I enjoy the process of reading books.

- Extrinsic reward: The reward for the activity is some external thing. Example: I read books because I receive money for each book I finish.

Outer Wilds is an experiment in how to motivate the player entirely through curiosity and to reward them solely with knowledge. The game doesn't have any extrinsic rewards for the player like badges, points, collected items, improved player stats, or even progress in the game world that persists across play sessions. When playing the game, the only lasting impact is the player's increased knowledge about the game world. One way to look at it is that the player doesn't change Outer Wilds, Outer Wilds changes the player.

Evidence of this design is that if I started Outer Wilds from the beginning now, I could beat it within 30 minutes. I'm only able to beat it so quickly because I've acquired the relevant knowledge about the game by spending a couple of dozen hours playing it.

From the perspective of designing learning experiences, I find this very interesting for a couple of reasons:

- I think some of the best learning experiences are driven by curiosity and rewarded by knowledge which is precisely the kind of experience design that is explored by Outer Wilds.

- Self-determination theory has found evidence that extrinsic rewards hurt intrinsic motivation1. To illustrate what this means, let's revisit the example about reading books:

- January. Suppose Eva reads books purely because she enjoys the books themselves — there's no extrinsic reward involved.

- February. Eva's parents want to encourage the reading habit so, for the month of February, they reward her with $10 for every book she completes — they've introduced an extrinsic reward.

- March. Eva stops receiving money for reading. According to the findings of self-determination theory, the extrinsic reward harmed Eva's intrinsic interest in reading. Consequently, she is less interested in reading and reads less than she did in January, back when she had never received an extrinsic reward for reading and read just for the fun of it.

Outer Wilds serves as an example of how to design an experience where players are motivated without extrinsic rewards. Such designs avoid the potential side effect of hurting the player's intrinsic enjoyment of the activity itself.

Experiential growth mindset2

Here are some rough definitions of fixed mindset and growth mindset:

- Fixed mindset: When you have a fixed mindset about something, you believe that you cannot get better at it. Example: You believe that you are "not a math person", you cannot get better at math, and so you don't bother trying to get better at math. Mistakes are very upsetting.

- Growth mindset: When you have a growth mindset about something, you believe that you can get meaningfully better at something by working at it over time. Example: You see that you are currently not very good at math but believe that, by practicing, you can get much better at it over time. Mistakes serve as clues as to how you could improve.

When I first heard of these ideas, I didn't find them to be very interesting. I thought: "Aren't these ideas obvious? Of course I have a growth mindset! I believe I can get better at whatever I set my mind to! I don't need to spend any more time thinking about these terms."

Several years later, I happened to encounter these terms again and noticed their connection to some of my own thinking and experiences. I realized that I had much to gain from more deeply internalizing the idea of a growth mindset. For one thing, my previous attitude showed that I had a fixed mindset about my growth mindset!

Here's one example to illustrate. When I give a presentation at work and ask for feedback on how it could have been better, the emotional part of my brain could certainly use improvement in the growth mindset department. The emotional part of my brain hopes that everybody says my presentation was perfect and it gets upset by any critical feedback it hears. Intellectually, I want this feedback because I know it'll help me to improve but that does little to comfort the emotional part of my brain. If the emotional part of my brain had more of a growth mindset, instead of getting upset by feedback, it'd get upset by the absence of feedback — "I put all this time into making this presentation and I hardly grew at all because nobody gave me any advice on how I can improve!" In the extreme, a growth mindset means obsessing over your rate of improvement.

The process of learning with a growth mindset could be summarized as3:

- Do. Make an attempt at something.

- Fail. Observe the mistakes you made.

- Learn. Use the mistakes as clues as to improvements you can make for your next attempt.

Outer Wilds provides players with an interesting way to develop a growth mindset. It doesn't include any instruction about growth mindset or explicitly mention it in any text in the game. I haven't even seen the game designers mention the phrase "growth mindset" in any of their talks or written documents! Yet the game gives players the opportunity to develop a growth mindset through their experiences and through observing it in role models:

- Experiences. When you're playing Outer Wilds and you die, you can think of that as failing. Outer Wilds makes failing very cheap. The penalty for dying is virtually zero — you merely return to your spawn point. The benefit of dying is that you may have learned something new about the game world. In sum, failing has an upside and virtually no downside. So the first things Outer Wilds does to facilitate a growth mindset are making failing cheap and even rewarding it. Another thing Outer Wilds does is it makes dying essentially necessary for acquiring certain knowledge. For example, the way that I learned that my character, a member of the Hearthian alien species, needs to wear a spacesuit in order to go into space was by going into space without a spacesuit and dying! There are less obvious lessons that also require dying that I won't list here to avoid spoiling the game.

- Role models. Throughout the game, the player encounters the writings of the Nomai, an advanced alien species that regularly mentions their scientific experiments in their writings. Kelsey Beachum's talk mentions that the Nomai have a cultural attitude that failure is progress and that this attitude comes through in their writings. I think this is a neat idea — helping the player to develop a growth mindset by surrounding them with a culture where a growth mindset is the norm. Observing these role models may help the player to internalize a growth mindset.

Emphasis on player autonomy4

A rough definition of autonomy is that it is about having the opportunity to make decisions for yourself. Autonomous and controlled are at opposite ends of the same spectrum. It's a subtle topic. I'll share a few points to give a taste of what autonomy means:

-

Blind compliance and blind defiance are not autonomous behaviors:

- Blind compliance: you do something primarily because somebody tells you to do it.

- Blind defiance: somebody requests that you do something and you do the opposite primarily because you feel like rebelling.

To be autonomous, you have to decide for yourself what you want to do. You need to consider your options, consider the consequences, and then take your action.

-

Being autonomous does not mean that you cannot seek assistance from others.

I find designing for autonomy to be very interesting because self-determination theory has found its presence to be important for a person's motivation.5

Outer Wilds is very much an exploration in how to design for player autonomy.

The game never explicitly assigns the player any objectives. Instead, the game world is filled with things that are designed to pique the player's curiosity6 and to provide the player with the opportunity to make discoveries through pursuing that curiosity. It's entirely up to the player to decide what they find interesting and then to pursue it.

More concretely, piquing the player's curiosity can be viewed as getting the player to ask their own questions and then embark on finding answers to those questions. Here are some examples (SPOILER ALERT: don't read this bulleted list if you'd like to avoid some minor spoilers):

- The player lands on a planet, sees a building that they've never visited, and asks themselves "what's inside that building?" It's a simple technique but it was effective at piquing my curiosity. We could call it seeing a distant object.

- As the player explores the planets, they find writings about people's experiences visiting the Quantum Moon. The player has never been to the Quantum Moon and doesn't even know how to get there. The more Quantum Moon references they encounter, the more they want to visit. They ask themselves: "How do I get to the Quantum Moon? What will I find when I get there?" We could call this technique hearing about a distant object.

- The player encounters three computer screens side-by-side. One screen has a disc in it and is displaying some text. The other two screens are blank and have empty disc drives. The idea is to get the player to wonder and ask themselves: "how do I get the other two computer screens to display their messages?" We could call this technique instances that don't match a pattern.7

- The player encounters an old note from an engineer that says they weren't able to get the probe cannon to launch. Then the player encounters a nearby computer screen that says that the probe cannon launched successfully. The intention is to get the player to ask themselves: "why do these pieces of information contradict each other?" We could call this technique contradicting information.

The game has essentially zero required tasks. The only required task occurs at the beginning of the game where the player needs to talk to the museum curator to get the launch codes for their spaceship. Other than that, the game doesn't require anything of the player. With the launch codes in hand, the player can explore any part of the game world that they choose — the game is designed to be explorable in any order.

Playtesting revealed that, after acquiring the launch codes, some players were uncomfortable with the lack of an explicitly assigned objective. They didn't want to launch into space without knowing their specific mission. The team solved this by holding the player's hand a little to get them used to the process of deciding on their own objectives. The solution was for the museum curator to ask the player, "Tell me, what's your plan once you're in space?" and the player can respond from one of these choices8:

- "I'm going to learn more about the Nomai."

- "I'll meet up with the other travelers."

- "I want to go somewhere no one's gone before."

- "I think I'll start with something small."

- "I don't know."

- "I'm gonna wing it!"

This solution supports the player's autonomy in that it asks the player what they want to do rather than telling them what to do. Although the player is not required to follow through on the choice they selected, the developers observed that players often do follow through. A benefit of the multiple choice response format is that it gives the player some ideas of what's possible in case their mind was blank in terms of what they should do next. I think this is a neat alternative to assigning the player an explicit objective.

Architecting for the piquing of curiosity and the pursuit of knowledge

Outer Wilds is designed to give the player the experience of curiosity-driven exploration which has this structure:

- Evoke the player's curiosity and give them a clue as to how they can pursue it should that be of interest to them. The player becomes curious about something in the game and formulates their own question about it. This thing provides a clue as to how the player can go about answering their question. Importantly, at no point does the game explicitly assign the player something to do — the player decides for themselves that they want to investigate their question.

- Intentional exploration. The player explores with the intention of answering their question. The player does not explore aimlessly.

- Rewarded solely with knowledge. The player finally uncovers the answer to their question. Their sole reward is knowledge.

To achieve this experience, the game was architected with a web of Curiosities and Clues:

- Curiosity. A special object that holds the answer to one of the game's major narrative questions. It is located in a hidden or hard-to-reach place so it requires several pieces of knowledge to access. It is linked with three Clues each of which is located on a different planet.

- Clue. Tells the player about the existence of a Curiosity and conveys a piece of knowledge needed to access that Curiosity. It also contains hints about how to find the Curiosity's other Clues.

That was the original design but it turned out to be messier in practice. Sometimes there's a Clue that points to a Clue that points to a Curiosity. In some cases, there are Clues that don't point to other Clues.

The web of Curiosities and Clues teaches the player about the game world and points the player to more things they might want to explore. The player can revisit this information at anytime via the game's ship log.

The fact that the conveyance of knowledge plays such a significant role in the game introduces an interesting design problem: how does the player know what information is relevant to making progress in the game and what information is ignorable? Here are some of the techniques the game uses to solve this:

- Informational areas of the game have interesting features while all other areas are visually boring. For example, an informational area on a planet might contain some buildings the player can enter whereas an area without any information might be an expansive treeless grassy plain. When playing the game, the player gets the sense that they should explore the buildings and ignore the plain.

- Every snippet of text in the game contains actionable knowledge. In other games, the player might encounter text that is just lore — it might convey story or set the atmosphere but it's irrelevant to making progress in the game. This is not the case in Outer Wilds: every snippet of text that the player encounters includes some tidbit that they can use.

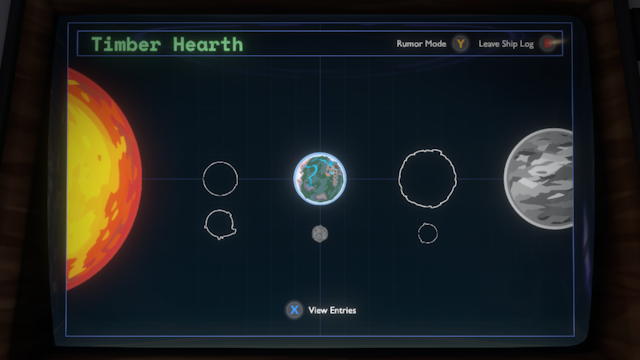

Ship log: a map of the player's knowledge

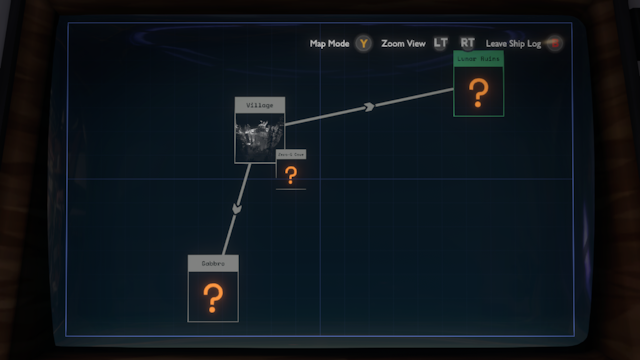

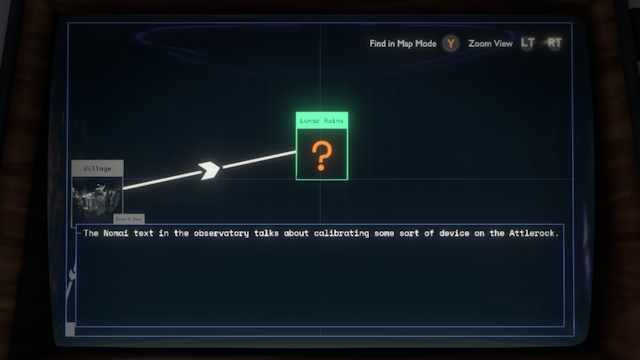

The ship log is a 2D map that is an external representation of the player's knowledge. The map is populated as the player makes discoveries. Items that the player has explored are visually distinct from those that the player has heard about but has yet to explore. For example, unvisited items might be represented by a question mark. In this way, the ship log communicates both what the player has learned and what they might want to explore next.

Below are some screenshots from shortly after I started a new game that describe the ship log in detail.

As I played through the game, the ship log served several uses for me:

- A record of what I know. As I was working on my latest goals, I could refer to the ship log to remind myself of things that I had already learned.

- Clues about what I don't know. Whenever I wanted to choose a new thing to explore, I could look at the ship log and select from one of the blank spots on my map. It was also motivational: "I want to go find out more about this unknown area!"

- A sense of progress. As my map was populated with more and more of the things I had discovered, I could look at my map and think: "Wow, look at all the things I've discovered!"

It seems to me that this could be a neat tool to incorporate into the design of a learning experience. As mentioned above, it can serve as a reference, convey clues of what one might want to learn next, and convey a sense of progress. Here are some other neat attributes of a map of knowledge:

- It's a reference that grows with the learner. The map grows as the learner grows.

- If the learner is using the map throughout their learning journey, it seems plausible the learner would become intimately familiar with the map and its contents as though it was a close friend.

- Because the map starts off nearly empty and grows gradually, it's likely to be approachable to the learner. Compare this with the learner receiving a full map of what they're going to learn — there's so much new stuff on there that it's likely to be overwhelming!

- The unknowns on the map serve to evoke the learner's curiosity — "I want to learn this! I want to learn that!"

- The map conveys the big picture as well as the relationships between the concepts.

Concluding thoughts

The back cover of Why We Do What We Do by Edward Deci (1995) says:

Instead of asking, "How can I motivate people?" we should be asking, "How can I create the conditions within which people will motivate themselves?"

It seems to me that this is exactly a question Outer Wilds explores through its design constraints of avoiding extrinsic rewards and explicitly assigned objectives.

If you're interested in designing learning experiences that prioritize intrinsic rewards, curiosity, knowledge, the learner asking and pursuing their own questions, autonomy, and a growth mindset then Outer Wilds seems like a potentially fruitful case study.

External links

Alex Beachum created the initial version of Outer Wilds as a part of his USC Interactive Media & Games Division master's thesis:

- 📕 Outer Wilds: A Game of Curiosity-Driven Space Exploration by Alex Beachum (2013). Alex's master's thesis (30 pages).

Later, Alex and a team of people invested several more years of work into Outer Wilds turning it into a production-quality award-winning game:

- 🎮 Outer Wilds (2019). The game.

Here are some resources that give insight into the design of Outer Wilds and the process of its creation:

- 🎥 Designing for Curiosity in Outer Wilds by Alex Beachum (2019). Talk by Alex who is the Director of Outer Wilds and worked on its design and narrative.

- 🎥 Sparking Curiosity-Driven Exploration Through Narrative in 'Outer Wilds' by Kelsey Beachum (2021). Talk by Kelsey who worked as a key narrative designer on Outer Wilds.

- 🎥 The Making of Outer Wilds by Noclip (2020). Documentary about the making of Outer Wilds.

Reach out

If you have any questions or are interested in anything you read here, feel free to leave a comment or reach out to me directly!

-

The potential negative effects of extrinsic rewards is a subtle topic.

On the one hand, my personal experiences are largely consistent with self-determination theory: my most fulfilling and long-lasting learning experiences have been driven by intrinsic rewards like curiosity and the pleasure of making things. Whereas when my learning has involved extrinsic rewards like grades, I tended to focus on the reward at the expense of the learning. My dedication to the topic lasted only until I received my final letter grade.

On the other hand, I'm not sure what to make of the research. There was a back and forth debate between two researchers in the field, Deci and Cameron. I like the following snippet from game developer Chris Hecker. It both articulates well my sense of confusion on the research and pulls a sensible conclusion out of it. The snippet is from over 10 years ago so I would have hoped that we would have gained some clarity since then but I'm not sure.

To hack my way out of the thicket, I focused on the two results that both sides seem to begrudgingly agree are true.

For interesting tasks,

- Tangible, expected, contingent rewards reduce free-choice intrinsic motivation, and

- Verbal, unexpected, informational feedback, increases free-choice and self-reported intrinsic motivation.

[...]

[T]he Flora paper heavily quotes the Cameron meta-analysis, which has been discredited by Deci, which was questioned by Cameron, which was responded to by Deci, and on and on. As I discuss in the slides, it's really hard to know who or what to believe. This is why I use the two conclusions above, because they are the only points on which Cameron and Deci seem to agree.

If anyone has any better ideas on what to make of the research, leave a comment or send me a message.

If you're interested in learning more about the potential negative effects of extrinsic rewards, here are some resources you can explore:

- 📕 Why We Do What We Do: Understanding Self-Motivation by Edward L. Deci (1995)

- 📕 Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A's, Praise and Other Bribes by Alfie Kohn (1993)

- 📕 Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us by Daniel H. Pink (2011)

- 🎥 Achievements Considered Harmful? by Chris Hecker

-

If you're interested in learning more about the concept of a growth mindset, see the book Mindset: The New Psychology of Success by Carol Dweck (2006).

↩ -

The phrasing "Do. Fail. Learn." is borrowed from Build: An Unorthodox Guide to Making Things Worth Making by Tony Fadell (2022)

↩ -

If you're interested in learning more about the relevance of autonomy, competence, and connectedness to motivation, here are some resources you can explore:

- 📕 Why We Do What We Do: Understanding Self-Motivation by Edward L. Deci (1995)

- 📕 Punished by Rewards: The Trouble with Gold Stars, Incentive Plans, A's, Praise and Other Bribes by Alfie Kohn (1993)

- 📕 Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us by Daniel H. Pink (2011)

-

To be more complete, self-determination theory has found the following factors to be key psychological human needs. The presence of these is important for a person's motivation:

- Autonomy. The opportunity to make decisions for yourself.

- Competence. The opportunity to improve your skills and knowledge.

- Connectedness. The opportunity to connect with others that share your interests.

-

The design of Outer Wilds attempting to pique the player's curiosity reminds me of the five Great Lessons from Montessori schools. These are stories about major historical developments: the origins of the universe, life, humans, numbers, and language. A primary purpose of the stories is to pique the curiosity of the children and inspire them to pursue the specific parts that interest them. For more details see Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius by Angeline Lillard (2017).

↩ -

Here's an example of instances that don't match a pattern causing a physicist to ask and pursue an important question:

↩James Maxwell discovered an important electromagnetic phenomenon essentially because a missing term broke a nice pattern in a set of equations.

— Changing Minds: Computers, Learning, and Literacy by Andre diSessa (2000), p. 17

-

This design of Outer Wilds asking the player what they want to do and giving them a few choices reminds me of an aspect of the design of Montessori schools. Each day, each child selects from a small list of possible activities. This gives them a sense of autonomy without being overwhelming due to the list of options being too large. For more details see Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius by Angeline Lillard (2017).

↩

View Comments

View Comments